|

| Source Wikipedia |

Name is the means of reference to all living and non-living things. Any object known to person is given a reputation to explain and communicate ideas about it. The name may be different in different languages and at different places. The art of naming the thing is understood as nomenclature and when it involves naming of plants it's called botanical nomenclature.

The process of naming plants supported international rules proposed by botanists to make sure a stable and universal uniform system is named botanical nomenclature.

Common Names

Common name is the name of the plant in a particular area or locality given by the people of that particular area. Such names vary from place to put and language to language. In India the name changes with the dialect.

Scientific Name

Scientists suggested name in such a way that it is accepted in the world and is used internationally. But again, the problem remains the same, i.e., the language which is not universal. So the botanists agreed to lay down certain rules and conditions. The main suggestion was that the language of the name should be in Latin. Botanical Latin is an international language used by botanists the world over for naming and describing plants. It originates from the Latin of the Roman plant writers, notably Pliny the Elder (A.D. 23-79). The Swedish botanist Carolus Linnaeus (1707-79) formally established the tradition that all plants should be given Latin names (or names of Latin form) and that works relating to them should also be in Latin. It is because:

1. Latin is a dead language, so the meanings of words do not change in the same way as those for living languages.

2. Botanical, Latin is very descriptive, with many terms for shape, texture and colour.

3. Latin does not inspire the political jealousies that might emerge if botanists were to convert to, say, English or Spanish.

During 1600 to 1850 AD Europe, particularly Greece, had dominated the planet of science. The script was Roman but language was Latin

BINOMIAL NOMENCLATURE

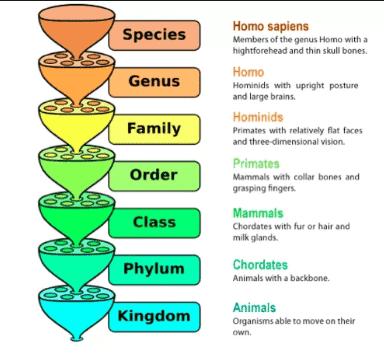

Linnaeus for the first time proposed that every living being has a binomial name, i.e., a name with two epithets. One is generic and therefore the other is restricted epithet. If an organism features a variety also, then the name becomes trinomial. Linnaeus proposed some rules for generic names of plants in Critica Botanica (1737) and Fundamental botanical (1736). A.P.de Candolle for the first time proposed rules for nomenclature of plants which were passed by International Botanical Congress at Paris (1867). Swedish Naturalist Linnaeus who started naming plants in 1753 as Binomial names. It was published in his book ―Species Plantarum.

The generic name is usually a noun showing colour, name or adjective, e.g., Sarracenia named after a scientist Michel Sarracin. Species is usually an adjective, e.g., for white flower, it's alba., for edible one it's sativa, black colour-nigrum etc.These names aren't used always.

Species could also be a Pronoun, e.g., americana, indica, benghalensis, etc. It may be shape of a leaf (character of plant), e.g., sagittifolia, name of other scientist to whom the plant is devoted , e.g., Sahnii etc. >>>>>Read More

The generic name is usually a noun showing colour, name or adjective, e.g., Sarracenia named after a scientist Michel Sarracin. Species is usually an adjective, e.g., for white flower, it's alba., for edible one it's sativa, black colour-nigrum etc.These names aren't used always.

Species could also be a Pronoun, e.g., americana, indica, benghalensis, etc. It may be shape of a leaf (character of plant), e.g., sagittifolia, name of other scientist to whom the plant is devoted , e.g., Sahnii etc. >>>>>Read More

INTERNATIONAL CODE FOR NOMENCLATURE OF ALGAE, FUNGI AND PLANTS

At the middle of 18th century, plant names were generally polynomial consisting of several words in a series. Carolous Linneaus proposed the elementary rules in Philosophia Botanica in 1751. In 1813 A.P.de Candolle proposed details of the principles regarding plant nomenclature in Theorie elementaire de la botanique. Alphonse de Candolle son of A.P.de Candolle convened an assembly of botanists of the world to present a new set of rules. Candolle convened the primary International Botanical Congress at Paris in 1867. The International Code for Nomenclature of Algae, Fungi and Plants (ICN) passed by Melbourne Congress was earlier known as International code Botanical Nomenclature (ICBN).

(1) Paris Code (1867)

The first International Botanical Congress was held at Paris in August 1861. About 150 American and European Botanists were invited to form laws for Botanical Nomenclature (Lois de la nomenclature botanique). The laws were called Paris code, as they were adopted at Paris . According to this code, the starting-point, for all nomenclature was fixed with Linnaeus.

Paris code has many inherent defects. After some years the American and British Botanists deviated from the rules and started following a new rule called Kew Rule.

(2) Rochester Code (1892)

N.L. Britton headed the Botanical Congress at Rochester, New York, USA in 1892. The Paris code was modified and with new recommendations, it had been called as Rochester Code. Some important recommendations were

(i) Strict adherence to Principles of Priority.

(ii) Acceptance of alternate bionomials resulting from employment of the principles of priority even in case of tautonyms.

(iii) Establishment of the sort concept to determine the right application of names.

(3) Vienna Code (1905)

The 3rd International Botanical Congress was held at Vienna in June 1905. In this congress, it had been established that Linnaeus Species Plantarum (1753) is that the start line for naming vascular plants. Nomina generica conservenda by which generic names having a wide use would be conserved over earlier but less well known names. Tautonyms are banned and the names of new taxa to be accompanied by Latin diagnosis.

(4) American Code (1907)

The botanists who proposed Rochester Code were dissatisfied with Vienna Code and refused to accept it in 1907. They modified the Rochester code to American Code. American code doesn't subscribe the principle of Nomina generica conservenda or the need of Latin diagnosis. It accepts type concept. In American Code, a binomial cannot be used again for a plant in any way either has been employed previously for another plant.

(5) Brussels Code (1912)

It recognizes the type concept and classification of the Vienna rules.

(6) Cambridge Code (1935)

The difference between American code and Vienna code was removed at the fifth Botanical Congress held at Cambridge (1930). The provisions suggested in this code are as follows:

(i) Type concept should be pursued.

(i) Type concept should be pursued.

(ii) A list of Nomina generica conservanda should be provided.

(iii) Tautonyms should be discarded.

(iv) Latin diagnosis of plants is important after January 1, 1932.

(7) Amsterdam Code (1947

Sixth International Botanical Congress was held at Amsterdam in 1935. In this a major change in the rules was made, i.e., from January 1,1935 names of new groups of recent plants, (except Bacteria) are to be considered as validly published only when they have a Latin diagnosis.(8) Stockholm Code (1952)

For the first time the word ‗Taxon‘ was introduced to designate any taxonomic group or entity.

(9) Paris Code (1956)

Here, the rule of compulsion of Latin diagnosis was scraped out and it had been decided that it should be published in English, French and German languages.

(10) Montreal Code (1961)

9th International Botanical Congress held at Montreal in August 1959, where a committee was appointed to review the question of conservation of family names. Nomina familiarum conservandafor Angiospermae was introduced. The code also assersted that the naming of fossil plantsshould also follow an equivalent lines as those of recent ones.

(11) Edinburgh Code (1966)

According to it, for family names the starting point should be A.L.de Jussieu‘s Genera Plantarum (1789). A new committee formed to figure upon the preparation of Glossary of technical terms which was called An Annotated Glossary of Botanical Nomenclature.

(12) Seattle Code (1972)

11th International Botanical Congress met atnSeattle in August 1969. The code was published in 1972 by F.A. Stafleu.Code introduced a replacement word Autonym, i.e., automatically established names.(13) Leningrad Code (1978)

The out comes were published in 1978.The code does not apply for bacteria. Principle of automatic typification was extended to the names of taxa above family rank, etc.

(14) Sydney Code (1983)

13th Botanical Congress was held at Sydney in August 1981 and the outcomes were published in 1983.

(15) Berlin Code (1988)

14th International Botanical Congress was held at Berlin in 1986 and the outcomes were published in 1988. Nomina Specifica Conservenda was introduced in the congress. Articles 66 and 67 were removed. In this two species names common wheat Linn, and tomato P .Miller were conserved against the principles of priority as these names were used widely.

(16) Tokyo Code (1994)

15th International Botanical Congress held at Yokohama in Japan in 1993. The code was translated into Chinese, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Russian and Slovak.

(17) St. Louis Code (1999)

This code is also available in many languages. The code is split into Rules, Articles and proposals . Rules are set up to put the nomenclature of the past into order and to provide space for the future.

(18) Vienna Code (2005)

17th International Botanical Congress was held in Vienna, Austria, July 2005.(19) Melbourne Code (2011)

The XVIII International Botanical Congress held in Melbourne, Australia in July 2011 made variety of very significant changes within the rules governing what has long been termed botanical nomenclature, although always covering algae and fungi also as green plants. This edition of the Code embodies these decisions; the first of which that must be noted is the change in its title. This edition of the code changed the title of the code as International code for Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants Recommendations deals with subsidiary points. According to it in future the names not following the recommended ones are rejected. Rules and proposals apply for all living and fossil organisms and fungi but don't include Bacteria.What is the new name of I.C.B.N?

it was formerly known as International code of botanical nomenclature. But when Vienna Code of 2005 is replaced by Melbourne code of 2011 it is known as the International botanical Congress.

International code of nomenclature of bacteria

For (ICNB) Bacteria, International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria was proposed separately. Presently, the rules and recommendations of Vienna code which were proposed by J. McNeill et al in 2005 are in practice.

What do you mean by botanical nomenclature?

The present International Code of Botanical Nomenclature (Lanjouw, 1956) is the result of many years of trial and error. 1956 edition of the code gives detailed instructions on the steps to be taken when any change appears necessary. It is interesting to note that during the last three or four International Botanical Congresses there have been, but few changes, except perhaps in the rearrangement of the code and in some less important points of nomenclature. The ICBN is based on Linne‘s own ‗Philosophia Botanica‘, when he lays down the main points of nomenclature in the form of aphorisms (principles). The code is divided into three clear parts, principles, rules and recommendations. In addition there are a few interesting appendices. The principles are basic points on which the code is based. They do not give detailed rules about nomenclature, but show the main ideas that have guided the compilers of the code, and should be kept in view by any botanist attempting to publish a new taxon.

Some Important Rules and Recommendations

1. All those plants which belong to one genus must be designated by the source generic name (Rule 213)

2. He who establishes a replacement genus should provides it a reputation (Rule 218)

3. the precise name must distinguish a plant from all its relatives (Rule 257)

4. Size does not distinguish species (Rule 260)

5. the first place of plant doesn't give specific difference (Rule 264)

6. A generic name must be applied to every species (Rule 284)

7. the precise name should follow the generic name (Rule 285)

0 Comments

If you have any query let me know.